Dan's instructions before the check ride were to use weather

information to (a) convince him that I understood it, (b) assess the

"soarability" of the day, and (c) apply the weather information to

plan a cross-country flight to Avenal. (He's given the last few

applicants the task of going to Williams, so I guess it was for

variety.)

On Saturday, I pulled all the weather I thought relevant from

aviationweather.gov. There's a good index page there

(http://aviationweather.gov/stdbrief/) that has many of the components

of the standard briefing. I started with national charts, went to

regional satellite imagery, read the area forecast, made sure that I

knew about active SIGMETs and AIRMETs. I settled on a tentative route

of flight to Avenal, and then pulled TAFs and METARs along the route.

To plan the flight itself, I used the Oakland RAOB sounding and

estimated that lift would go to 6,500 feet. I marked up an old

sectional chart with circles to plan the flight route. With all that

done, I called WX-BRIEF to make it official, and learned that two GPS

satellites were out of service and there were no TFRs that would

affect me.

So, heading into the check ride, I had a folder that had:

- Reminder to bring photo ID

- Student certificate

- Knowledge test report

- Printouts of the questions I got wrong on the knowledge test

- All the weather information: my own summary, plus printouts of the charts

- Current sectional and terminal charts

- Weight & balance calculation for 81C

- Dan's fee :)

In addition to all the paperwork, I wanted to be sure that I had

absolutely everything I might possibly need:

- I brought food for the ground crew; if you'd been out yesterday,

you'd have had a chance to try my herb foccacia

- Water - two vacuum bottles with cold water, plus my 3L hydration pack

- Water, part 2: since we were out, I brought 12 bottles of water for

the crew (it was all I could readily carry)

- A kneeboard with checklists. Dan likes written checklists. I found

that they helped me stay focused on doing everything I needed to and

that my checkride nerves were not affecting me.

- My portable air compressor, given the fun we had with the tailwheel

on 16Y on Sunday. (No, we did not need it.)

The big day!

I planned to arrive at Byron at 8:30 in the morning. As it turns out,

I was a little early. I knew it would be necessary to get a weather

briefing before takeoff, so I ran through the same set of stuff on

aviationweather.gov and put my laptop to sleep. As with Saturday, I

called flight services for a weather briefing and took notes. I

picked a good day for the check ride. The area forecast was for a

12,000 foot ceiling and unlimited visibility throughout California.

About the only thing that mattered was the winds aloft forecast.

Winds were out of the north.

The oral exam...

Dan started by making sure the paperwork was in order. When he asked

for ID, I gave him his choice of three types: my driver's license,

passport, or a DHS trusted traveler card. He took the driver's

license.

As part of checking the paperwork, he noted my score on the knowledge

test (57 out of 60) and I volunteered to show him the questions I had

missed. He dismissed two of them as "the sort of tricky questions

they used to ask." Since I had studied those questions, I could

explain why I was wrong, what the right answer was, and in one case,

why I probably wouldn't have gone flying with the facts set out in the

question.

The last question was about hyperventilation, which was a dumb mistake

on my part. From there, we moved to aeromedical factors in general

(hyperventilation, dehydration, hypoxia), all of which are dangerous

because they affect what you fly the airplane with -- your brain. I

talked about some of my experiences hiking (dehydration), my traffic

conflict with the Twin Otter last fall (hyperventilation avoided), and

my last wave flight (hypoxia).

We started off talking about weather, in part because of a joke I told

him. I'd been in Chicago last week, and there was a horrendous storm.

6-8 lane freeways were down to one lane in each direction, and there

were cars being towed out of parking lots. Our field engineer in the

area is a private pilot (ASEL right now, working on commercial and

instrument ratings, and he has a flight instructor friend who owns a

Socata TBM and lets him ride along on angel flights). We decided that

the Chicago weather had gone beyond a mere convective SIGMET and

really should have been called a "biblical SIGMET."

I went through what amounted to a weather briefing with Dan, going

through printouts of the weather products and interpreting them. Dan

told me that the G-AIRMET printouts, which put AIRMETs on a map

graphically, were an experimental product a year ago. I find them way

easier to use than the text AIRMETs, which is why I had them printed

out.

When we discussed the RAOB sounding, I showed him that I'd obtained a

thermal index prediction at http://www.soarforecast.com/. He told me

that the TI had been developed on the east coast, and you can

generally fly up to about -1 or -2. However, on the west coast, we

have a more arid climate and we can often go to a TI of zero. That

segued into a discussion of how thermals form and what affects them

(type of terrain, vegetation, height, flatness or lack of it) and the

route of flight I'd planned to Avenal.

Lots of discussion on the chart. Based on the weather, I didn't think

I could make Avenal, and with lift predicted only to about 6,500,

there weren't a lot of public airports I could use for diversion. We

discussed special use airspaces, and Dan pointed out several things

that he wanted me to explain on the sectional.

He asked me to draw a stick figure diagram of the pitot-static system

and a TE vario. Based on my description of the TE system, he asked

about my background (physics), and told me that there was one exam he

administered once to an Air Force pilot. He asked about the

pitot-static system, and got back a long answer with all kinds of

subtlety, and discovered that his candidate was the lead pitot system

instructor for the USAF.

Next, I had to reproduce the mountain wave diagram. As it turns out,

I didn't get all of the nuances. What he's looking for is an

understanding that you have to have wind increase with altitude, that

there is ridge lift upwind, where the primary wave is, and that the

primary wave will incline towards the obstruction. He wrote an

article for Soaring magazine. Read it and know it better than I did.

The last thing I remember talking about on the oral was weight and

balance and aircraft performance. I showed him my W&B calculation,

and he asked about what would happen if the balance was too far

forward (the nose will be heavy, which would increase the likelihood

of a PIO in a Grob) and too far aft (stall recovery is

harder/impossible). Dan said that he met Gerhard Waibel -- the "W" in

"ASW-27" -- at a conference once, and Waibel told him that the ASW-20

was designed to fly with the CG farther aft than the limit placed on

it in the POH because aviation authorities are conservative. He asked

why that might be, and I was able to deduce that it was a reduction in

induced drag from the elevator.

Enough talking, it's time to fly...

My preflight was a little scattered. I have a rhythm down well after

flying for so long, but I did the laminated checklist in 81C in order

to be double-plus-sure that I didn't miss anything. This resulted in

some extra walking around the plane, but I figured extra walking was

better than missing something.

After preflight, I looked at the windsock, and winds were favoring 30.

AWOS said that wind was 340 @ 12, gusting 18.

Before the first tow, I briefed Paul on tow speeds, where we intended

to release, and asked him for a long straightaway after 1500 AGL to

begin tow maneuvers. I asked Paul to offset left on liftoff because

my turn into the wind would be to the right. With no skydiving on

Monday, it was safe to use a left offset. Before climbing into the

ship with Dan, I asked if he wanted me to do the passenger briefing on

my checklist. He said that my checklist was complete and he would

count that as fulfilling the requirement. I had a great safety

briefing prepared, with such gems as "We won't need to bail out.

Nobody has bailed out of an NCSA ship in the history of the club, and

the only reason I would forsee doing so is if the glider caught fire.

Fiberglass doesn't burn." (Yes, when I fly Virgin America, I secretly

wish I could have been part of the writing team for their safety

video, which is on YouTube. I highly recommend it.)

I also went over the emergency plan:

- Up to 50 feet, land straight ahead

- 50-200 feet, land off to the left in the old airport

- 200 feet, return to runway 12. Because of the gust factor, I

planned to use a speed of 57 (best L/D) + 6 (gust factor), and aim for

the runway threshold. Dan noted that ground speed would be quite

high, which I took as a hint he wasn't going to make me do the 180

turn.

- 450 feet, abbreviated pattern

- 800 feet, normal pattern

On the first tow, we lifted off, and I was nervously watching the

altimeter because I was expecting the rope to break at 200 AGL. It

didn't. We turned crosswind, and I expected the rope to pop out at

~500 feet. It didn't. On upwind, there were several bumps, and the

vario briefly blipped to about 8-9 kt up, so I was porpoising a little

bit while maintaining tow position. We departed the pattern over the

IP at about 900 feet, and I was wondering why we had gotten such a

strong checkride rope that was still in one piece (maybe it exceeded

200% of "checkride strength"?) when 16Y's left wing lifted up. I

prepared for the gust to lift my left wing, but it didn't, and 16Y

rolled back the other way.

Apparently, we ordered our Scout with intermittent checkride

mechanical problems. Kind of like how my father used to order cars

with the "intermittent mountain steering" option so he could head for

a cliff and run his hand over the top of the steering wheel.

I don't know what kind of control inputs Paul was putting in, but it

was really, really obvious. The first roll was so big that when my

wing didn't get lifted, I knew what was up. With the rockoff, I

released, entered downwind, and flew a normal pattern, bringing the

plane to a stop at the first turnoff. Paul had landed on Magical

Runway 5, and was ready to go. At least, I think runway 5 was

magical, because the towplane's mechanical problem was all repaired,

and we were ready for the next tow.

The second tow was much less eventful. We lifted off, and I called

the decision points along the way up. At 1500 AGL, I boxed the wake.

There were some pretty good thermals, so I held each of the corners

for a couple of seconds to show that I had control of the plane. Dan

did a couple of slack lines, but they were much easier to recover from

than the slack lines than I've received from instructors. We released

at 3500 feet over Discovery Bay. Dan had me do some straight stalls

and turning stalls, which I did after clearing the area. After a

couple of steep 180s, he asked me to fly at MCA, then minimum sink,

then speed to fly. My kneeboard with all the V-speeds made it much

easier to not let the checkride environment have me forget stuff. He

told me that the rest of the flight was mine, and I found a 6-8 knot

thermal that I wasn't able to center really well. In spite of that, I

managed to gain 1,000 feet and find a bunch of zero-sink air. (Van

had prepped SS, and called for a radio check, so I told him where we'd

seen the lift.)

At 1,500 feet, he asked me to enter the pattern. By the time I was

ready to turn base, I was at 1,200 feet, so I opened full spoilers on

base, and noted that I'd throw in a slip to lose altitude after

turning final. (I was expecting a spoiler malfunction, but I guess

all the checkride gremlins took up residence in the towplane

yesterday.) I landed in a slight slideslip to correct for the

crosswind.

After bringing the glider to a stop just before the first turnoff, Dan

said that we'd take one more flight and called for a pattern tow.

Just after liftoff, the rope popped out. I lowered the nose, got back

to flying speed, and cracked the spoilers to settle in and bring it

down. As I turned off the taxiway and rolled to a stop, Dan

congratulated me.

Special thanks to everybody who made this happen:

- Terence, for driving me to get it done. Ever since you signed me

off for solo, there's always been something on the list: check out in

the 1-26, get the knowledge test done, fly ever weekend, schedule the

check ride... I hope you're satisfied now, at least for a couple more

weeks. :)

- Paul, for towing yet another milestone of mine. You've been the tow

pilot for my first solo, my first flight in a single-place glider, and

now my first rating.

- Mike Schneider, John Randazzo, and John Boyce. After your simulated

check rides, Dan's was a cake walk!

- Bob Ferguson and John Randazzo for being ground crew on a work day

Next up for me, I'll be doing a backseat checkout so that when I fly

people who are on my "give a ride to" list, they can sit up front.

This summer, I have resolved to start flying in the mountains (watch

out, Larry, I'm coming for you!). With a private certificate, I now

meet the requirements for thermal camp. Before then, I may take some

spin training at Williams.

Matthew

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

Monday, April 22, 2013

Mang flies to Tracy at the end of the day,Saturday

I learned a ton flying over to Tracy. It always seemed so far away/unknown before... but 12 miles is really not that far! With Tracy so close it seems like a great opportunity for people to get their feet wet for XC.

I did a bunch of prep for the flight that included looking at the AF/D, sectional, Google Earth and asking other pilots with experience about the airport. I had safe glide circles set up and Tracy loaded into my flight computer.

I called the Tracy AWOS on the phone and the winds were favouring 30. I went over the plan with the tow pilot. We would tow straight out towards Tracy then he'd land ahead of me. Looking at the airport in the AF/D and Google Earth there are turnouts at each side at midfield on runway 30. Talking to Buzz revealed that you can turn out on the median between the runway and taxiway as long as you watch out for the runway lights.

We towed out towards Tracy and by the time we reached about 3,500' we were about halfway there and with a tailwind had Tracy in easy glide. At the halfway point you can actually see both airports. We arrived at Tracy with plenty of altitude and had a chance to overfly the field and get a good look at the airport before landing (this seems like a good idea when landing at a new place!) It was quiet at Tracy... all we heard on the CTAF was good old 16Y and some traffic at other airports.

The plan was to stop as soon as possible after touchdown to minimize the distance Buzz and I would have to push back the glider. My landing was ok but what with focusing on making a good approach I more or less forgot to get it stopped quickly and ended up taking the midfield turnoff (rather than trying to go into the median between the lights).

So I got to learn a new trick! With just two people it's easiest to push the G103 backwards, with each person on the wing inside of halfway or one person on the nose and another on a strong part of the leading edge. That way both people can push and you're positioned to push down on the nose to turn.

We did another pattern, this time opting to land downwind. It was a little different landing downwind on a foreign runway... definitely need to watch those angles rather than looking for familiar landmarks.

We did another tow back towards Byron, this time getting off around 3,900' about halfway to Byron. We found a little lift and scratched around for about an hour before finally landing back at home!

Great learning experience and it will be great to get checked out for XC and start reaching into the hills around Tracy (the clouds there often look good!)

Here's the trace of the flight back. You can see we got off tow about halfway and the initial glide back to Byron was basically a piece of cake:

Thanks to Buzz for entertaining the idea and for all the pushing.... next time I'll land closer to where we want to be ;)

- mang

Here's an annotated image I made using an app called Skitch on the Mac (available in the app store). It lets you easily do a screen capture and annotate i

Here's an annotated image I made using an app called Skitch on the Mac (available in the app store). It lets you easily do a screen capture and annotate i

__,_._,___

Monday, April 8, 2013

Dan Colton one of newest members introduces himself

Hi to NCSA from your newest member.In way of an introduction let me first say that my flying interest go way back. I was introduced to flying back in High School, taking hang gliding lessons in Monterey on the sand dunes above the beach and taking rides from a friend in a Cessna 152 out of Watsonville. A few years later I got my glider license at Sky Sailing in Fremont back in 1980 and a few years later I got my airplane license. Needless to say I much prefer gliders to airplanes which is what brought me to your club. My other interests include riding my bike, sailing and or course, watching my 14 year old daughter play soccer.This past weekend at Work Day was fun and I enjoyed meeting so many of the club members and learned a lot about glider maintenance and assembly. I am very excited to be joining NCSA and look forward to spending time with all of you both on the ground and in the air. Amongst my flying goals are thermal camp and wave camp in the Sierras, dual cross country instruction, and flying with my new friends in NCSA at Truckee. I hope to see you at the field and in the air.Dan Colton

--

Monique

Friday, March 29, 2013

Terence's Friday Soaring Report ,North Wind Wave day - with thanks to Ramy - March 22, 2013

Ramy called a north wind wave day for Friday and Paul very kindly offered to get out to the airport early to support Ramy's audacious attempt to fly downwind to Santa Barbara.

Ramy launched around 9am and connected with the Los Vaqueros wave at WAVE3. Soon after Walter and I tried to do the same in KP, but we didn't see any lift worth taking, so we exercised patience and stayed on tow until WAVE1 where smooth 2kt lift was found. As you will notice from the flight trace, we attempted to find better than 2kt lift to the east and west of WAVE1 but no joy.

Walter alerted Ramy on 123.3 that WAVE1 was working and he soon joined us and out-climbed KP. We took about 1.2 hours to reach 18,000 where the wave gave hints that it was getting stronger. Had NorCal granted us higher, I think we could have made 20K+.

After topping out and hearing Ramy head south, we decided to burn up some altitude by exploring West, however, NorCal wanted us out of there:

"1KP, I'm vectoring SFO departures around you, state intentions"

Time to cut and run- we turned around and headed towards Tracy. On the way back a different NorCal controller inquired "say type of aircraft" and we had to repeat "glider" several times. Cognitive dissonance I suppose. No one expects a glider to be at 15,000 feet.

By the time we got back the winds were blowing strong at Byron- 320 23G28. Walter made an excellent low energy landing, despite getting smacked around on short final.

Many thanks to Paul for getting up early on his day off to make it happen for us. Yesterday was definitely a top 10 flight for me. And thanks to Ramy for the encouragement.

Cheers,

Terence

__._,_.___

__,_._,___

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

High Altitude Chamber Ride in OKC

NCSA club rules specify that: ":Members who fly at altitudes higher than

18,000' are required to have attended a high altitude FAA-USAF

physiological training course." This was easy to arrange until some

years ago, as the nearby Air Force Bases offered these courses several

times a year and initially only cost $20 or less. When this was no

longer an option, members could do what Walter did last year and go to

Van Nuys for the 'normobaric training', where there was no pressure

change, which remains at sea level. The oxygen level is controlled via

piped air which the trainee breathes through a mask, to simulate a climb

to high altitude. The only other option for this training is through

the FAA CAMI in Oklahoma City.

Maja chose that option and describes her experiences:

"Hi all,

For civilian pilots who want to test their own tolerance to hypoxia in

the controlled environment, only two kinds of options are available

these days:

a)going to CAMI - Civilian Aeronautical Medical Institute in Oklahoma

City, an FAA establishment, for a hypobaric and hypoxic chamber ride or

b) commercial normobaric hypoxia testing in Van Nyues in Southern

California or few other and more distant places.

CAMI high-altitude chamber ride obviously means hypoxia with

concomittant decompression, as if one is really climbing in the

atmosphere. Normobaric testing, like in Van Nuys, means ground level

pressure at all times, and the oxygen-starved air is supplied via the

face mask.

The other relevant difference between these two options is the

distribution of cost for the test and travel. CAMI offers morning of

lectures and a chamber ride plus the spatial disorientation course with

the simulator the same afternoon for zero dollars. Two hour normobaric

testing in SoCal was close to $300. Travel to OKC does cost money,

though: but if one flies to Dallas and then drives the rental car to

OKC, that costs about $300. A night in the hotel is needed for either

option. So, finances being about the same, I have opted for the hypoxia

physiology training in CAMI in Oklahoma City.

For those who have never done it, "the chamber" really is a sealed

walk-in chamber, fits about 12 students plus 2 staff. It is connected

via valves in the walls to large compressors (?) which can take out or

whoosh in the air at different speeds and of different O2 pressure.

The first part of the "ride" takes you to 5000 ft AGL and back to ground

level, at 3000 ft/min (just like lazy Byron thermal), as a test of the

health of ones sinuses and ability to clear the ears. Whoever finds this

part painful should leave the chamber, because it will only get worse

after that. First real "ascent" is to 8000 ft (3000 ft/min), O2 mask

hanging on the wall above your left shoulder. About that altitude an

unannounced rapid decompression (10-15 s) to 18.000 ft occurs and one

has to recognize that moment and jump for the O2 mask. This is supposed

to simulate the loss of cabin door in an airliner. Such a rapid

decompression is a very violent sensation, at least it was for me, so

there is really no way that it cannot be noticed.

What follows is the real test of your hypoxia tolerance. Masks on, we

"climbed" to 25.000 ft at 3000 ft/min. Once 25.000 ft is reached, half

of the students take off the masks for up to 5 min, while the other half

sitting across with masks on and watching and writing down symptoms they

see in other people. Everyone has a worksheet, most important part of

which is to check your symptoms during the first, second ... fifth

minute while without the O2 mask. The goal is to identify 3-4 symptoms,

some more some less obvious. However, the moment one has a very obvious

symptom the mask should go back on, and you should record both that

symptom and the O2 saturation reading from the pulse oxymeter. I had

identified 3 symptoms, all within the first minute: blurry vision - not

too obvious, very obvious heart racing, and finally rapidly developing

dizziness. The last made me put the mask back on at 47 s: did not think

I could detect anymore symptoms if I actually fainted.

After that I "enjoyed" watching men getting silly by refusing to put the

mask back on. At the end of minute 3, it looked like the collective IQ

of all the students which still had the mask off was about 70. They

grinned very happily when addressed by staff, but could not execute the

simple tasks given, like stretch your arms and pretend to fly around.

Some could execute tasks - one guy was asked to put plastic pieces into

his hood or front of the sweatshirt, which he did quite well, but later

could not recall that it was him who did it, rather the staff person.

Temporary amnesia is apparently common in hypoxia. Eventually, all these

men needed help to put the O2 masks back on. Time of useful

consciousness at 25.000 ft is said to be between 3-5 minutes. However,

if one cannot put the mask back on, that consciousness if not very

useful. Two minutes at 25.000 ft without O2 seemed like a better

approximation, which was also mentioned during the morning lectures.

The last test was back at 18.000 ft for five minutes, demonstrating the

effect of hypoxia on night vision. Once the lights were out, we were

given a chart with 5-color printed pin-wheels (color vision testing),

with "Z"s around the periphery (peripheral vision testing), and small

sectional chart legends to focus on (foveal focusing). I did not think I

noticed much of an effect of O2 deprivation on night vision: could still

tell apart yellow from white and green from neighboring blue, could see

all "Z"s and focus on most of the text. It's just that it became much

easier when I put the O2 mask back on: the colors got brighter, and I

could tell apart more of those sectional chart legends.

Other interesting tidbits: 1)For CAMI, one needs a current FAA Medical,

which can be older than 1 year (mine was). 2) The session is recorded on

a video (ours wasn't by mistake), so if you end up being really silly it

will go to YouTube and go viral around the globe :-)

3) Men with beards: if you have one like President Larry, it will be

hard to seal the O2 mask to your face; goatees and mustaches are manageable.

4) I was the only female in the group.

If one can afford taking couple of days off during the work week to go

to OKC, it is definitely worth it. I learned a lot: I have not expected

those particular symptoms of hypoxia that I have noticed. Also, even

though I thought I would be more susceptible to hypoxia than most men, I

did not think I could "last" only 47 sec. Teachers and instructors are

doing a good job, and I found it useful to do it in a large and

interactive group of people.

Maja

Links for you:

http://www.faa.gov/pilots/training/airman_education/aerospace_physiology/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypobaric_chamber

------------------------------------

Yahoo! Groups Links

<*> To visit your group on the web, go to:

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/norcalsoaring/

<*> Your email settings:

Individual Email | Traditional

<*> To change settings online go to:

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/norcalsoaring/join

(Yahoo! ID required)

<*> To change settings via email:

norcalsoaring-digest@yahoogroups.com

norcalsoaring-fullfeatured@yahoogroups.com

<*> To unsubscribe from this group, send an email to:

norcalsoaring-unsubscribe@yahoogroups.com

<*> Your use of Yahoo! Groups is subject to:

http://docs.yahoo.com/info/terms/

18,000' are required to have attended a high altitude FAA-USAF

physiological training course." This was easy to arrange until some

years ago, as the nearby Air Force Bases offered these courses several

times a year and initially only cost $20 or less. When this was no

longer an option, members could do what Walter did last year and go to

Van Nuys for the 'normobaric training', where there was no pressure

change, which remains at sea level. The oxygen level is controlled via

piped air which the trainee breathes through a mask, to simulate a climb

to high altitude. The only other option for this training is through

the FAA CAMI in Oklahoma City.

Maja chose that option and describes her experiences:

"Hi all,

For civilian pilots who want to test their own tolerance to hypoxia in

the controlled environment, only two kinds of options are available

these days:

a)going to CAMI - Civilian Aeronautical Medical Institute in Oklahoma

City, an FAA establishment, for a hypobaric and hypoxic chamber ride or

b) commercial normobaric hypoxia testing in Van Nyues in Southern

California or few other and more distant places.

CAMI high-altitude chamber ride obviously means hypoxia with

concomittant decompression, as if one is really climbing in the

atmosphere. Normobaric testing, like in Van Nuys, means ground level

pressure at all times, and the oxygen-starved air is supplied via the

face mask.

The other relevant difference between these two options is the

distribution of cost for the test and travel. CAMI offers morning of

lectures and a chamber ride plus the spatial disorientation course with

the simulator the same afternoon for zero dollars. Two hour normobaric

testing in SoCal was close to $300. Travel to OKC does cost money,

though: but if one flies to Dallas and then drives the rental car to

OKC, that costs about $300. A night in the hotel is needed for either

option. So, finances being about the same, I have opted for the hypoxia

physiology training in CAMI in Oklahoma City.

For those who have never done it, "the chamber" really is a sealed

walk-in chamber, fits about 12 students plus 2 staff. It is connected

via valves in the walls to large compressors (?) which can take out or

whoosh in the air at different speeds and of different O2 pressure.

The first part of the "ride" takes you to 5000 ft AGL and back to ground

level, at 3000 ft/min (just like lazy Byron thermal), as a test of the

health of ones sinuses and ability to clear the ears. Whoever finds this

part painful should leave the chamber, because it will only get worse

after that. First real "ascent" is to 8000 ft (3000 ft/min), O2 mask

hanging on the wall above your left shoulder. About that altitude an

unannounced rapid decompression (10-15 s) to 18.000 ft occurs and one

has to recognize that moment and jump for the O2 mask. This is supposed

to simulate the loss of cabin door in an airliner. Such a rapid

decompression is a very violent sensation, at least it was for me, so

there is really no way that it cannot be noticed.

What follows is the real test of your hypoxia tolerance. Masks on, we

"climbed" to 25.000 ft at 3000 ft/min. Once 25.000 ft is reached, half

of the students take off the masks for up to 5 min, while the other half

sitting across with masks on and watching and writing down symptoms they

see in other people. Everyone has a worksheet, most important part of

which is to check your symptoms during the first, second ... fifth

minute while without the O2 mask. The goal is to identify 3-4 symptoms,

some more some less obvious. However, the moment one has a very obvious

symptom the mask should go back on, and you should record both that

symptom and the O2 saturation reading from the pulse oxymeter. I had

identified 3 symptoms, all within the first minute: blurry vision - not

too obvious, very obvious heart racing, and finally rapidly developing

dizziness. The last made me put the mask back on at 47 s: did not think

I could detect anymore symptoms if I actually fainted.

After that I "enjoyed" watching men getting silly by refusing to put the

mask back on. At the end of minute 3, it looked like the collective IQ

of all the students which still had the mask off was about 70. They

grinned very happily when addressed by staff, but could not execute the

simple tasks given, like stretch your arms and pretend to fly around.

Some could execute tasks - one guy was asked to put plastic pieces into

his hood or front of the sweatshirt, which he did quite well, but later

could not recall that it was him who did it, rather the staff person.

Temporary amnesia is apparently common in hypoxia. Eventually, all these

men needed help to put the O2 masks back on. Time of useful

consciousness at 25.000 ft is said to be between 3-5 minutes. However,

if one cannot put the mask back on, that consciousness if not very

useful. Two minutes at 25.000 ft without O2 seemed like a better

approximation, which was also mentioned during the morning lectures.

The last test was back at 18.000 ft for five minutes, demonstrating the

effect of hypoxia on night vision. Once the lights were out, we were

given a chart with 5-color printed pin-wheels (color vision testing),

with "Z"s around the periphery (peripheral vision testing), and small

sectional chart legends to focus on (foveal focusing). I did not think I

noticed much of an effect of O2 deprivation on night vision: could still

tell apart yellow from white and green from neighboring blue, could see

all "Z"s and focus on most of the text. It's just that it became much

easier when I put the O2 mask back on: the colors got brighter, and I

could tell apart more of those sectional chart legends.

Other interesting tidbits: 1)For CAMI, one needs a current FAA Medical,

which can be older than 1 year (mine was). 2) The session is recorded on

a video (ours wasn't by mistake), so if you end up being really silly it

will go to YouTube and go viral around the globe :-)

3) Men with beards: if you have one like President Larry, it will be

hard to seal the O2 mask to your face; goatees and mustaches are manageable.

4) I was the only female in the group.

If one can afford taking couple of days off during the work week to go

to OKC, it is definitely worth it. I learned a lot: I have not expected

those particular symptoms of hypoxia that I have noticed. Also, even

though I thought I would be more susceptible to hypoxia than most men, I

did not think I could "last" only 47 sec. Teachers and instructors are

doing a good job, and I found it useful to do it in a large and

interactive group of people.

Maja

Links for you:

http://www.faa.gov/pilots/training/airman_education/aerospace_physiology/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypobaric_chamber

------------------------------------

Yahoo! Groups Links

<*> To visit your group on the web, go to:

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/norcalsoaring/

<*> Your email settings:

Individual Email | Traditional

<*> To change settings online go to:

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/norcalsoaring/join

(Yahoo! ID required)

<*> To change settings via email:

norcalsoaring-digest@yahoogroups.com

norcalsoaring-fullfeatured@yahoogroups.com

<*> To unsubscribe from this group, send an email to:

norcalsoaring-unsubscribe@yahoogroups.com

<*> Your use of Yahoo! Groups is subject to:

http://docs.yahoo.com/info/terms/

Friday, March 15, 2013

Bruce Wallace is a newish club member who recently soloed, He is writing to introduce himself to NCSA members.

If you know anything about me, being brief is not one of my

attributes. So, with that in mind I'll tell some stories about my

experiences in Scotland in parts, to give readers a little break. I

won't talk about solo in Byron first.

Part I, cloud flying:

To begin, I was sent by my company to Scotland in 1975 to support 4

small computer systems. Each weighed more than 500 lb and were

generally not that reliable. There was no one in Britain qualified to

work on them. They were sent there as software development tools for the

programmers on a smaller system built locally. At some point the

university of St Andrews(programmers) may come in to the story, their

graduates are formidable.

I found myself in Scotland, a qualified pilot and owner of a

C-150(N7203X). I went to a local airport and discovered that renting

airplanes was over the top expensive, but also found there was a gliding

club about 30 miles north of Edinburgh near loch Leven. That club was

and is the Scottish Gliding Union, its near a small village Portmoak.

This club could be transported to Byron and you would not notice a

significant difference. The club had a single employee, and she managed

the airport/farm during the week and was the cook on weekends. Otherwise

it was an "all hands on deck" operation, if you flew you needed to help.

So, on to cloud flying. I had been a member of this club for a

couple of months. I may or may not have gone solo at that point, its not

relevant to this story. I was at the club one weekend when a young

pilot went off in a single seat Pirat(SDZ), he was probably 20 and I was

old, maybe 30. This glider actually had some electrical stuff on board.

None of the other gilders had radios, or other electrical

paraphernalia. The Pirat had an electric turn and bank gyro powered by

a pair of dry cells. This gyro was invented by the Sperry company about

1920 plus-minus a couple of years and was the first to be used in

airplanes. Prior to that flying in clouds was a death wish.

On that day there were layers of clouds around about 2000-3000 agl,

maybe 50% cover. Anyway, the young man went off in the Pirat and later

found himself well above the cloud level. Eventually he needed to

return to the airport, but a cloud deck had moved in below him. He

descended through the clouds and landed normally. On landing he seemed

quite wound up and animated. He had figured out that he had connected

the battery backward, so when the gyro said left, the gilder was going

right. He said he really needed to concentrate when descending through

the cloud to not misinterpret the gyro. Well, imagine the little fly

wheel in the gyro spinning backwards due to reversing the polarity of

the battery, and the gyro is giving you bogus info, and imagine knowing

that to fly trough clouds.

Afterward I was left with doubts, what about flying through the clouds,

what about that? Generally I didn't sense any interest in this. I made

some discrete inquires about this. I was told that cloud flying in

Scotland was ok, as long as it was outside airways. Remember I'm an

alien in Scotland. So I asked what about midair's? I was told, not from

the young man, we use "natural separation". Natural separation was

described as the low probability of two aircraft in the same cloud.

More parts to follow on request.

B.W.

_____________________________________________________________

Netscape. Just the Net You Need.

attributes. So, with that in mind I'll tell some stories about my

experiences in Scotland in parts, to give readers a little break. I

won't talk about solo in Byron first.

Part I, cloud flying:

To begin, I was sent by my company to Scotland in 1975 to support 4

small computer systems. Each weighed more than 500 lb and were

generally not that reliable. There was no one in Britain qualified to

work on them. They were sent there as software development tools for the

programmers on a smaller system built locally. At some point the

university of St Andrews(programmers) may come in to the story, their

graduates are formidable.

I found myself in Scotland, a qualified pilot and owner of a

C-150(N7203X). I went to a local airport and discovered that renting

airplanes was over the top expensive, but also found there was a gliding

club about 30 miles north of Edinburgh near loch Leven. That club was

and is the Scottish Gliding Union, its near a small village Portmoak.

This club could be transported to Byron and you would not notice a

significant difference. The club had a single employee, and she managed

the airport/farm during the week and was the cook on weekends. Otherwise

it was an "all hands on deck" operation, if you flew you needed to help.

So, on to cloud flying. I had been a member of this club for a

couple of months. I may or may not have gone solo at that point, its not

relevant to this story. I was at the club one weekend when a young

pilot went off in a single seat Pirat(SDZ), he was probably 20 and I was

old, maybe 30. This glider actually had some electrical stuff on board.

None of the other gilders had radios, or other electrical

paraphernalia. The Pirat had an electric turn and bank gyro powered by

a pair of dry cells. This gyro was invented by the Sperry company about

1920 plus-minus a couple of years and was the first to be used in

airplanes. Prior to that flying in clouds was a death wish.

On that day there were layers of clouds around about 2000-3000 agl,

maybe 50% cover. Anyway, the young man went off in the Pirat and later

found himself well above the cloud level. Eventually he needed to

return to the airport, but a cloud deck had moved in below him. He

descended through the clouds and landed normally. On landing he seemed

quite wound up and animated. He had figured out that he had connected

the battery backward, so when the gyro said left, the gilder was going

right. He said he really needed to concentrate when descending through

the cloud to not misinterpret the gyro. Well, imagine the little fly

wheel in the gyro spinning backwards due to reversing the polarity of

the battery, and the gyro is giving you bogus info, and imagine knowing

that to fly trough clouds.

Afterward I was left with doubts, what about flying through the clouds,

what about that? Generally I didn't sense any interest in this. I made

some discrete inquires about this. I was told that cloud flying in

Scotland was ok, as long as it was outside airways. Remember I'm an

alien in Scotland. So I asked what about midair's? I was told, not from

the young man, we use "natural separation". Natural separation was

described as the low probability of two aircraft in the same cloud.

More parts to follow on request.

B.W.

_____________________________________________________________

Netscape. Just the Net You Need.

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Matthew joins Walter and Terence on a tour of Oakland ARTCC tour!

At the last minute, I was able to add myself to the Oakland Center

tour that Walter arranged with his retiring neighbor.

The short version: It was awesome.

The long version:

I've never visited an ATC facility before, and in my time flying with

NCSA, I've only needed to contact ATC once, back when we tried to do a

transponder check on 81C by contacting Norcal. When Walter sent out

the invite, I couldn't resist seeing the other side of the mic.

ZOA manages airspace from about halfway down the California coast up

to almost the Oregon border, plus a great deal of airspace out over

the Pacific Ocean. When you put in all the Pacific territory, it

manages about 11% of the earth's surface. I was surprised to learn

that missile test launches are routinely communicated to ZOA so they

can vector traffic around splashdown zones.

The highlight of the trip was a chance to talk with controllers in the

sector that handled traffic in the Reno area. The controller working

the Tahoe/Reno sector was not very busy. For quite some time, he had

a few VFR planes doing flight following, a couple of commercial

flights, and some military activity. (For some reason, the F-16s

moved across his scope really fast.) Walter, Terence, and I had a

chance to talk with him for quite some time in between work with the

aircraft in "his" airspace.

Each controller has a primary radar scope. IFR aircraft show up very

clearly, with a flight number and altitude. Computer systems work to

hand off aircraft between controllers and even between ATC centers,

and the computers automate the handoff. When an aircraft is tracked

using only primary radar returns, it's a small blip on the scope, and

it can come and go depending on whether terrain blocks the radar

returns. Sometimes terrain even causes radar returns, so at one point

the controller pointed at a blip on his scope and said "this is always

there, so I think it's a radar return off terrain." The scope did

have outlines for the wave windows near Tahoe, and had lines for the

localizers on each runway at Reno.

To become a sector controller, the training takes more than a year.

Before getting to work on your own, you have to be able to draw the

map of your area from memory, be familiar with daily weather patterns

as well as seasonal variations, and know the major flows through the

sector. Watching controllers at work, their experience clearly showed

through. I found the display to be kind of a jumble, and it was much

easier for me to track transponder returns than primary returns

because the transponder signals are displayed much more notably on the

radar screen. We did ask the controller what we could do as glider

pilots to help him do his job, and he said that transponder-equipped

aircraft are much more visible, and that visibility translated into

better separation. If he sees a glider operating out of Minden

intercepting the localizer to Reno, it's easy to send traffic around

something he knows is a plane at a certain altitude. The example he

gave is that if a glider is at 16,000 feet, he can hold a plane

descending into Reno at a temporarily higher altitude for separation

(17,000?) or give it a slight turn around the glider.

It was a great way to spend a morning (though I'm not sure my boss

would have agreed, which is why I didn't give him a choice). I'm glad

I was able to go before doing my first flying in the mountains this

summer.

Before you ask: there are no pictures. The pictures on Wikipedia are

pretty accurate, though. The lighting is fairly low to improve

readability of scopes, and it kind of reminded me of the way a Vegas

casino tries to keep the same light regardless of the actual time

outside. (Just way more important to life and safety than a Vegas

casino...)

Matthew

tour that Walter arranged with his retiring neighbor.

The short version: It was awesome.

The long version:

I've never visited an ATC facility before, and in my time flying with

NCSA, I've only needed to contact ATC once, back when we tried to do a

transponder check on 81C by contacting Norcal. When Walter sent out

the invite, I couldn't resist seeing the other side of the mic.

ZOA manages airspace from about halfway down the California coast up

to almost the Oregon border, plus a great deal of airspace out over

the Pacific Ocean. When you put in all the Pacific territory, it

manages about 11% of the earth's surface. I was surprised to learn

that missile test launches are routinely communicated to ZOA so they

can vector traffic around splashdown zones.

The highlight of the trip was a chance to talk with controllers in the

sector that handled traffic in the Reno area. The controller working

the Tahoe/Reno sector was not very busy. For quite some time, he had

a few VFR planes doing flight following, a couple of commercial

flights, and some military activity. (For some reason, the F-16s

moved across his scope really fast.) Walter, Terence, and I had a

chance to talk with him for quite some time in between work with the

aircraft in "his" airspace.

Each controller has a primary radar scope. IFR aircraft show up very

clearly, with a flight number and altitude. Computer systems work to

hand off aircraft between controllers and even between ATC centers,

and the computers automate the handoff. When an aircraft is tracked

using only primary radar returns, it's a small blip on the scope, and

it can come and go depending on whether terrain blocks the radar

returns. Sometimes terrain even causes radar returns, so at one point

the controller pointed at a blip on his scope and said "this is always

there, so I think it's a radar return off terrain." The scope did

have outlines for the wave windows near Tahoe, and had lines for the

localizers on each runway at Reno.

To become a sector controller, the training takes more than a year.

Before getting to work on your own, you have to be able to draw the

map of your area from memory, be familiar with daily weather patterns

as well as seasonal variations, and know the major flows through the

sector. Watching controllers at work, their experience clearly showed

through. I found the display to be kind of a jumble, and it was much

easier for me to track transponder returns than primary returns

because the transponder signals are displayed much more notably on the

radar screen. We did ask the controller what we could do as glider

pilots to help him do his job, and he said that transponder-equipped

aircraft are much more visible, and that visibility translated into

better separation. If he sees a glider operating out of Minden

intercepting the localizer to Reno, it's easy to send traffic around

something he knows is a plane at a certain altitude. The example he

gave is that if a glider is at 16,000 feet, he can hold a plane

descending into Reno at a temporarily higher altitude for separation

(17,000?) or give it a slight turn around the glider.

It was a great way to spend a morning (though I'm not sure my boss

would have agreed, which is why I didn't give him a choice). I'm glad

I was able to go before doing my first flying in the mountains this

summer.

Before you ask: there are no pictures. The pictures on Wikipedia are

pretty accurate, though. The lighting is fairly low to improve

readability of scopes, and it kind of reminded me of the way a Vegas

casino tries to keep the same light regardless of the actual time

outside. (Just way more important to life and safety than a Vegas

casino...)

Matthew

Friday, February 1, 2013

Boyang learns a useful lesson on a combined wave and thermal day - the worst of both worlds

Although this past Saturday was not nearly as epic as Sunday, the conditions made for an eventful flight. In the morning, lenticular clouds were hovering along the mountain range, right above the wind mills, indicating a wave day. There was even a rotor cloud over the pumping station. However, by the time FB was assembled and Van passed his checkride, all of the clouds had disappeared. Did the wave disappear as well? Terence and I set to find out.

Without the lenticular clouds marking the location of the wave, the first challenge is to find the wave. On this particular day, two things were in our favor. First, we already had a clue from events earlier in the day. Second, the standing wave nature of this means that areas of lift and sink change much slower than a thermal. Unfortunately, it isn't as simply as flying towards where we last saw the clouds. From the perspective of a person on the ground, a lenticular clouds looks the same whether you are viewing at it straight on or from an angle. This matters because the region of the lift is perpendicular to the direction of the wind. Since there is a 15 knot wind blowing straight down runway 23, I make a request for a high tow towards brushy peak.

Around 1500' on tow, we experienced a prolonged period of 2 knot climb rate. Normally, the climb rate on tow is 6 knots, so we were in some serious sink. On a wave day, this could be a blessing in disguise because that means the front of the wave might be only half a wavelength away. Sure enough, right around 3000 feet, we experienced a very nice lift, got off tow, and started doing figure eights. In a classic wave, there should be consistent lift with minimal turbulence. Flying a line between brushy peak and the reservoir, we went through patches of lift, followed by no lift and sometimes exuberant lift. It wasn't a classic wave, but wasn't a thermal either because flying in circles didn't help much.

Turning back to the airport, we flew over the pumping station, and found signs of a thermal. After a few adjustments, we found the sweet spot and started climbing at up to 6 knots. With some work we soon gained 1000 feet, and reached 3000' a few miles southeast of runway 30. Just when I thought I might be setting a personal record for longest flight from Byron, the vario went from positive 6 knots to negative 6 knots. Pretty soon, we lost all of the altitude we had gained, and set up for a landing. The culprit might have been a hiiden rotor clouds, which we saw right over the pumping station earlier in the day!

In conclusion, I learned a very useful lesson: on a wave and thermal day, you are not going to get the best of both world. In fact, you are probably going to get the worst of both worlds. Waves work best in stable air because stable air is conductive towards laminar flow of each sublayer of the wave. However, on a thermal day, the unstable air disrupts the laminar flow, and reducing the effectiveness of the wave. On the other hand, directly underneath a wave and on the back side of a wave, rotors lurk, which ultimately ended my flight. In hindsight, we should have taking a much higher tow to get above the thermals and go straight for a juicy wave.

Boyang

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Buzz breaks a myth - Riding high and far on Sunday, 300km myth broken!!! [9 Attachments]

-------- Original Message --------

| Subject: | [norcalsoaring] Riding high and far on Sunday, 300km myth broken!!! [9 Attachments] |

|---|---|

| Date: | Mon, 28 Jan 2013 21:34:49 -0800 |

| From: | Buzz Graves <buzz.graves@gmail.com> |

| To: | Norcal Soaring <norcalsoaring@yahoogroups.com> |

| CC: | Buzz Graves <buzz.graves@gmail.com> |

[Attachment(s) from Buzz Graves included below]

It is very unusual to get farther than 300 km in January, but like is always said if you don't paddle in you will never know what the day can offer, Sunday will go down as a very special day. Nearly all the lift you read about was offered, thermals, convergence, streets aligned with the wind, and that magic wave that is so eerie smooth and exhilarating when you are literal on top of the world above the clouds.

As Ramy called the day , both the NAM and RASP from Avenal were showing a good potential for clouds and winds that were not going to stir things into a mess of turbulence. The whole time I was rigging the skies over the Diablo's to the south looked very inviting and as time passed stepping stones of other clouds were forming nearby. From the start you could see a large range in cloud bases with over a 1000ft difference. This usually means convergence, if you are trying to go far during this time of year where the days are the shortest, key is not turning and continue to go forward and start as early as possible. Goal for the day was to try and break the myth a flight over 300km in January was nearly impossible in thermals, maybe in wave but not otherwise.

Launching near 11:30 was the best I could do driving from Los Gatos with my glider in tow, rigging and all that overhead stuff. Moving fast I could I got help from Glider ground as I taxed by as the spotted my shoulder belt flapping in the breeze, thanks guys you are great!!! I took BG to slightly over 4000ft just south of 580 and then glided to the first cloud. Climb was slow, 1-2 knots with bases about 5000ft, not high enough to get into San Antonio Valley where the clouds bases were up to 7000ft. I headed to Mtn Oso keeping the valley strips in reach. Nearly every wisp was working, great when you are not all that high, only the lift was 2-3 knots so slow going. 300km was looking tough as the myth predicted. Further south things were looking better and better as the RASP predicted. As I neared San Carlos Res. there was a well marked cloud convergence line toward Los Banos and beyond. As I got in the area you could easily see how that was happening, valley air was converging with the airmass coming through Pacheco Pass at the 152 crossing, wind patterns on the reservoir were telling the story. This was a great run, not turning for mile after mile bring that 300km into the realm of possible. I continued south until a out and return would break the myth. Actually there was no end in sight for good clouds as the went beyond I could see at the Benito's, only end was when the sun would set and could you make it back in time.

The return had its tricky moments, the lower cloud bases near the reservoir ( 4000ft) wasn't enough to get to he higher clouds in San Antonio valley ( >7000FT) and a easy ride back north. This leg was an exercise in patience, 1-1.5 knots was good enough until you could stretch to he next good looking cloud over higher ground. It all paid off when I got close to Paradise Flats where the vario started sing those higher notes that tingle the spine, 4-6 knots to cloud base at over 7000ft and Bob's your uncle. Heading north in San Antonio Valley near cloud bases and not turning again was again bring that 300km day closer and possible. So time to relax and snack on the Starbucks sandwich. Get to Rel 2 I couldn't help bit turn around and finish the second half of my sandwich and enjoy the views. Back down to the reservoir and back north again. The nice clouds I came down on were looking different and so a bit more turning to move on.

Then as if a gift had been handed to me, just south of Mtn Stakes I found wave on the up wind side of some clouds running perpendicular to the wind. Smooth and easy to climb at 4-5 knots from 7000ft to top out at over 9000ft. On top of the world and feeling very the 300km was in the bag and maybe even more. Over most of the clouds heading north I had to pick cloud canyons to as I sunk lower and lower. Cloud bases near Rel 1 near Livermore were only about 5k. Looking further north Mtn Diablo was looking possible. Tanking up as much as possible near Meadow Lark I cross a big blue hole and then connect north of Los Vaqueros Then on to the next wisp coming ff the thermal plumes from the Antioch Power Plant.

Working the power plant plumes to 5k in 1-2 knots I headed across the delta till I had Byron in final glide to with a 1000ft margin over pattern. Getting back near Discovery Bay I meet up with Mathew in 972 looking really good in the late afternoon sun. Yep it was time for a photo shoot, hope you enjoy the pictures.

The myth has been broken with plenty of margin....OLC 395Km!!! A personal best for me in the month of January and maybe the longest flight from Byron as well this time of year.

It was a great day we all shared in many ways for those who paddled in, both on the ground and in the air,

Mahalo,

Buzz

Attachment(s) from Buzz Graves

9 of 9 Photo(s)

__._,_.___

__,_._,___

Thursday, January 10, 2013

Terence heeds SoaringNV's WAVE ALERT for Jan 9th - Fabien is eager to come along at least to see the Sierras up close...

Sierra Wave Trip Report - Minden 1-9-13

It all started (as it often does) with Ramy’s email to the NCSA list suggesting that members subscribe to Soaring NV’s Wave Watch email service. The service offers Kempton Izuno’s expert predictions of wave in the Sierra, as Ramy said, Kemp is very well regarded when it comes to forecasting wave and has accumulated a lot of empirical data over the years to help refine his forecasts.

Within a couple of days of subscribing a Wave Alert forecast popped up in my inbox forecasting a wave event for 1-9-13:

Minden, Nevada Wave Alert: Jan 9

This day-specific alert is because high confidence wave is coming within 3 days:

1) The forecast maps show a classic, low risk, wave producing structure:

o Winds steadily increase with altitude

o 11,000 ft., 40 knots@250 (ridgeline)

o 18,000 ft., 70 knots@250

o 30,000 ft., 100 knots@250

2) Relative humidity of 50-70%, going from 50% at dawn to 70% by sunset. This

is ideal as the lennies are obvious and the foehn gap is large.

3) Rain/snow arrive very late in the day, so sunrise to sunset looks open to fly.

4) The forecast is little

A quick call to Soaring NV (“envy”) and a discussion of the forecast with Laurie was all it took for me to commit to a dual flight in the ASK-21 with chief CFI Russell Holtz. (If the name rings a bell it’s because Russell wrote the Glider Flying Handbook). I had a chat with Russell the following day and confirmed that the forecast still looked great. Russell described the wave as “beginner wave”, meaning it would be well formed and marked, hopefully without strong rotor.

I mentioned my proposed trip to Fabien Bruning and he was interested in coming along for the ride, if nothing else to see the Sierra mountains up close for the first time. So at 5am Wednesday we were caffeinated and Minden bound on Interstate 80. By 7am we were in the mountains and the sun came up to reveal big fat lenticular clouds to the east:

Our excitement was building, but short-lived. The descent into Carson Valley revealed a blanket of thick fog. Despite a VFR TAF, the AWOS at Minden was reporting freezing fog and low IFR conditions with calm winds. Plan B: Breakfast number 2. iPhone says Cowboy’s Cafe is 3.5 stars, hit Navigate. Pow. 10 minutes later we’re ordering breakfast with the locals and discussing the unusual weather.

By the time we had finished breakfast the fog was gone and it was VFR unlimited. A quick drive to the airport and we’re greeted by Laurie, who is extremely welcoming and is happy to see us. A quick word on Soaring NV if you haven’t visited- the facilities are wonderful: comfy chairs, an awesome flight simulator setup, coffee, hot chocolate, snacks in the kitchen, free WIFI and a constant stream of friendly faces all eager to talk about soaring.

Russell soon arrived and apologized for being behind schedule because of the weather. After an intro flight Russell was back to give Fabien and I some ground instruction on wave flying. He started with an explanation of how a change in wavelength can shift the surface wind direction 180 degrees due to the rotor moving. He had just experienced this phenomenon on the previous flight- winds were from the NW on takeoff shifting to SW by the time he returned for landing. Lesson: always visually check the winds and listen to the AWOS. The departure runway may not be a good choice for landing.

On to our planned flight. There was a high possibility of climbing beyond the limit of the cannula O2 system, which is about 18K, so we would bring face masks and switch in flight. To save money (and for thrills) we would tow into the rotor, release in the rotor and climb using the rotor updrafts. Hmm, I thought. Is he pulling my leg? Negative. Oh and by the way, this is not a beginner wave day. The rotor is very strong. Strong enough to break the tow rope during one of the earlier launches.

We made our way out to the flight line and with some trepidation I buckled in and announced “my takeoff, I have the controls”. Five minutes later we entered the rotor and started taking a mild beating- a combination of random rolling moments, pitch changes and positive & negative accelerations strong enough to eject any loose object. Thirty seconds later the intensity doubled and I was having a lot of trouble maintaining position on tow, in the blink of an eye I was high above the Pawnee and Russell took the controls to get us back into position. WOAH! What just happened??? We got off tow and kept going up in the rotor, a minute later we hit the laminar flow of the wave. A bit like transitioning from Metallica to Mozart.

The wave at lower altitudes was not strong, but it was a consistent 2 knots. We zigged and zagged west of HWY 395, Russell emphasizing the importance of not getting blown downwind. With winds aloft at 50kts+ a lapse in concentration can lead to a long journey upwind back to the primary wave.

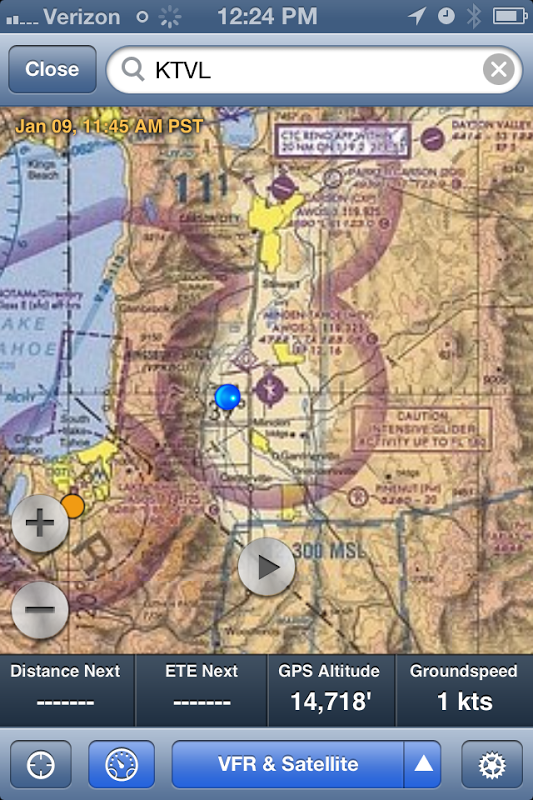

In the above moving map notice that Foreflight depicts our glider as a stationary blue dot because of our 1kt groundspeed. While maneuvering Russell and I had some laughs playing with groundspeed. At one point we were pointing at Lake Tahoe travelling east at 5kts. With these sorts of windspeeds every turn must be precise.

We were slowly gaining altitude, but just as the grass is always greener, there’s always better lift to be had somewhere else. We proceeded South to try and pick up some better lift from Monument Peak. Moving closer to the ridge the lift slowly died and turned into sink, but we didn’t give up hope, we just figured the primary wave was closer to the mountain. Slowly moving forward I expected the vario to reverse course at any minute, but it never did, so we cut our losses and headed north, maintaining a ground track just west of HWY 395. Soon we were back in steady 2kt lift that increased to 4kts as we moved north. Soon we were back in the game at 15,000 feet after losing about 4,000 during our exploration to the south. Climbing though 16,000 the vario indicated 8kts and it was time to call Laurie to co-ordinate opening the Wave Window with Norcal & Oakland Center. No response was heard after a couple of calls, most probably due to a cold battery. In the meantime the wave had strengthened and we were going up at 9kts and about to bust through 18,000MSL. I put the boards out to keep us legal, while Russell was trouble-shooting, but it was in vain, we could not establish radio contact. No go for the wave window.

Not being one to give up on the mission, I suggested that we get back on the ground ASAP and swap batteries. What followed was a simulated emergency descent from 18K to 5K that was nothing like the one I did with Mike Schneider in the 737 simulator in Dallas, let’s just say it was a little more “hands on”. A short time after getting back on the ground we had a fresh battery and were ready to launch back into the rotor. Compliments to Brad for getting us turned around so quickly. This time the rotor wasn’t as strong and I was able to maintain better position. I think.

Since we has already located the sweet spots on the previous flight, getting to 18K was not as challenging as the first go. At 17.5K Russell made the radio call to base and Laurie responded that the West Wave Window has been opened to FL280 until 5pm. Music to my ears, but not to Russell’s. Some loose tape was resonating and whistling quite loudly right in Russell’s ear. I can’t quite remember what Russell did to dampen the noise, but it got better. In the meantime I was having trouble switching tubes from cannula to face mask. With Russell’s help we got the tubes rigged and it was time to start climbing into the window.

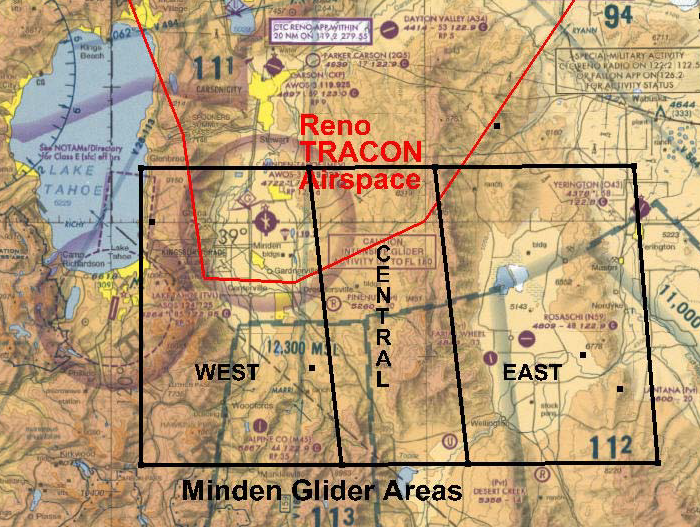

The wave windows are a product of negotiation between PASCO and Oakland ARTCC & NORCAL TRACON. For soaring pilots to have access to Class A airspace it’s important that flights stay within the lateral bounds of the windows (see below).

In our case Soaring, NV requested that the West Window be activated, since this was the location of the primary wave. Unfortunately, the strong lift that had taken us to 18K an hour earlier was weaker on the second visit. After slowly climbing to 21K, we decided to call it a day and give Fabien a shot before the moisture arrived.

We wrapped up with another full spoiler descent to the pattern and landed into a 20 knot SSW wind.

Back in the warmth of the Soaring, NV there was some fresh coffee waiting. I wasn’t sure whether to pour it on my feet or drink it. No matter how many layers of socks you wear, your feet will feel like ice blocks during a wave flight at these altitudes. All of the other layers of clothes seemed to work- plan on wearing long johns and a wool hat. While Fabien was in the air I described my flights to Kemp who had called to get an update on the conditions. I hope I was able to provide some useful data.

After Fabien returned we debriefed with Russell. The day had been good, but not as good as we had initially hoped for. The reason: the winds aloft had more of a southern component than expected, this had the effect of shredding the wave and creating a really gnarly rotor.

It was about 5pm and the storm was coming. Time to hit the road and get out of the mountains before the snow hit. We said our goodbyes and off we went.

Thanks very much to Laurie, Russell, Brad, Gabe & Kemp (did I miss anyone?) If you would like to fly in wave, Minden is the Mecca and it’s on our doorstep. What are you waiting for?

Terence Wilson

OLC Flight information

http://www.onlinecontest.org/olc-2.0/gliding/flightinfo.html?dsId=2812179

http://www.onlinecontest.org/olc-2.0/gliding/flightinfo.html?dsId=2812184

It all started (as it often does) with Ramy’s email to the NCSA list suggesting that members subscribe to Soaring NV’s Wave Watch email service. The service offers Kempton Izuno’s expert predictions of wave in the Sierra, as Ramy said, Kemp is very well regarded when it comes to forecasting wave and has accumulated a lot of empirical data over the years to help refine his forecasts.

Within a couple of days of subscribing a Wave Alert forecast popped up in my inbox forecasting a wave event for 1-9-13:

Minden, Nevada Wave Alert: Jan 9

This day-specific alert is because high confidence wave is coming within 3 days:

1) The forecast maps show a classic, low risk, wave producing structure:

o Winds steadily increase with altitude

o 11,000 ft., 40 knots@250 (ridgeline)

o 18,000 ft., 70 knots@250

o 30,000 ft., 100 knots@250

2) Relative humidity of 50-70%, going from 50% at dawn to 70% by sunset. This

is ideal as the lennies are obvious and the foehn gap is large.

3) Rain/snow arrive very late in the day, so sunrise to sunset looks open to fly.

4) The forecast is little

A quick call to Soaring NV (“envy”) and a discussion of the forecast with Laurie was all it took for me to commit to a dual flight in the ASK-21 with chief CFI Russell Holtz. (If the name rings a bell it’s because Russell wrote the Glider Flying Handbook). I had a chat with Russell the following day and confirmed that the forecast still looked great. Russell described the wave as “beginner wave”, meaning it would be well formed and marked, hopefully without strong rotor.

I mentioned my proposed trip to Fabien Bruning and he was interested in coming along for the ride, if nothing else to see the Sierra mountains up close for the first time. So at 5am Wednesday we were caffeinated and Minden bound on Interstate 80. By 7am we were in the mountains and the sun came up to reveal big fat lenticular clouds to the east:

Our excitement was building, but short-lived. The descent into Carson Valley revealed a blanket of thick fog. Despite a VFR TAF, the AWOS at Minden was reporting freezing fog and low IFR conditions with calm winds. Plan B: Breakfast number 2. iPhone says Cowboy’s Cafe is 3.5 stars, hit Navigate. Pow. 10 minutes later we’re ordering breakfast with the locals and discussing the unusual weather.

By the time we had finished breakfast the fog was gone and it was VFR unlimited. A quick drive to the airport and we’re greeted by Laurie, who is extremely welcoming and is happy to see us. A quick word on Soaring NV if you haven’t visited- the facilities are wonderful: comfy chairs, an awesome flight simulator setup, coffee, hot chocolate, snacks in the kitchen, free WIFI and a constant stream of friendly faces all eager to talk about soaring.

Russell soon arrived and apologized for being behind schedule because of the weather. After an intro flight Russell was back to give Fabien and I some ground instruction on wave flying. He started with an explanation of how a change in wavelength can shift the surface wind direction 180 degrees due to the rotor moving. He had just experienced this phenomenon on the previous flight- winds were from the NW on takeoff shifting to SW by the time he returned for landing. Lesson: always visually check the winds and listen to the AWOS. The departure runway may not be a good choice for landing.

On to our planned flight. There was a high possibility of climbing beyond the limit of the cannula O2 system, which is about 18K, so we would bring face masks and switch in flight. To save money (and for thrills) we would tow into the rotor, release in the rotor and climb using the rotor updrafts. Hmm, I thought. Is he pulling my leg? Negative. Oh and by the way, this is not a beginner wave day. The rotor is very strong. Strong enough to break the tow rope during one of the earlier launches.

We made our way out to the flight line and with some trepidation I buckled in and announced “my takeoff, I have the controls”. Five minutes later we entered the rotor and started taking a mild beating- a combination of random rolling moments, pitch changes and positive & negative accelerations strong enough to eject any loose object. Thirty seconds later the intensity doubled and I was having a lot of trouble maintaining position on tow, in the blink of an eye I was high above the Pawnee and Russell took the controls to get us back into position. WOAH! What just happened??? We got off tow and kept going up in the rotor, a minute later we hit the laminar flow of the wave. A bit like transitioning from Metallica to Mozart.

The wave at lower altitudes was not strong, but it was a consistent 2 knots. We zigged and zagged west of HWY 395, Russell emphasizing the importance of not getting blown downwind. With winds aloft at 50kts+ a lapse in concentration can lead to a long journey upwind back to the primary wave.

In the above moving map notice that Foreflight depicts our glider as a stationary blue dot because of our 1kt groundspeed. While maneuvering Russell and I had some laughs playing with groundspeed. At one point we were pointing at Lake Tahoe travelling east at 5kts. With these sorts of windspeeds every turn must be precise.

We were slowly gaining altitude, but just as the grass is always greener, there’s always better lift to be had somewhere else. We proceeded South to try and pick up some better lift from Monument Peak. Moving closer to the ridge the lift slowly died and turned into sink, but we didn’t give up hope, we just figured the primary wave was closer to the mountain. Slowly moving forward I expected the vario to reverse course at any minute, but it never did, so we cut our losses and headed north, maintaining a ground track just west of HWY 395. Soon we were back in steady 2kt lift that increased to 4kts as we moved north. Soon we were back in the game at 15,000 feet after losing about 4,000 during our exploration to the south. Climbing though 16,000 the vario indicated 8kts and it was time to call Laurie to co-ordinate opening the Wave Window with Norcal & Oakland Center. No response was heard after a couple of calls, most probably due to a cold battery. In the meantime the wave had strengthened and we were going up at 9kts and about to bust through 18,000MSL. I put the boards out to keep us legal, while Russell was trouble-shooting, but it was in vain, we could not establish radio contact. No go for the wave window.

Not being one to give up on the mission, I suggested that we get back on the ground ASAP and swap batteries. What followed was a simulated emergency descent from 18K to 5K that was nothing like the one I did with Mike Schneider in the 737 simulator in Dallas, let’s just say it was a little more “hands on”. A short time after getting back on the ground we had a fresh battery and were ready to launch back into the rotor. Compliments to Brad for getting us turned around so quickly. This time the rotor wasn’t as strong and I was able to maintain better position. I think.

Since we has already located the sweet spots on the previous flight, getting to 18K was not as challenging as the first go. At 17.5K Russell made the radio call to base and Laurie responded that the West Wave Window has been opened to FL280 until 5pm. Music to my ears, but not to Russell’s. Some loose tape was resonating and whistling quite loudly right in Russell’s ear. I can’t quite remember what Russell did to dampen the noise, but it got better. In the meantime I was having trouble switching tubes from cannula to face mask. With Russell’s help we got the tubes rigged and it was time to start climbing into the window.